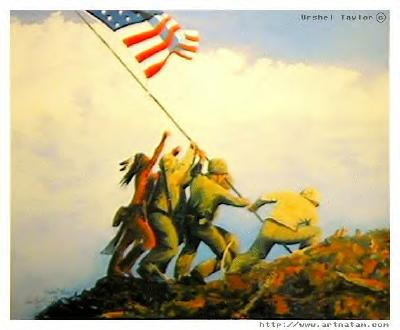

Ira Hayes

Many Americans will have heard of Ira Hayes, the Pima Indian who with his five mates in the Marine Corps raised the United States flag on Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima. He was in the photograph, now world-famous, taken by Joe Rosenthal. But Ira Hayes died of acute alcoholism in a cotton field on the Pima reservation on a night in January 1955. He lay all night on the cold ground and death was attributed to "exposure." What had happened in the ten years intervening since the dramatic moment on Mount Suribachi?

Mount Suribatchi

On November 12, 1953, the Arizona Republic, the Phoenix morning newspaper, reported that Hayes spent the previous night in jail on a drunk-and-disorderly charge. The reporter did some digging in the files, and found that this was the forty-second occasion that Hayes had been arrested on such a charge. There would be still other arrests between November, 1953, and January, 1955.

He had served throughout the South Pacific, fighting at Vella Lavella and Bougainville before coming up to Iwo Jima, where he served for thirty-six days and came out unwounded. After the flag-raising incident he and two of his buddies were brought back to the United States to travel extensively in support of the seventh war loan.

One of these buddies reported that Hayes refused to be leader of a platoon because, as he explained, "I'd have to tell other men to go and get killed, and I'd rather do it myself." He was reluctant to return home, but he was given no choice. That started a round of speaking engagements, parades, ticker tape -- and people offering hospitality. The hospitality, unfortunately, invariably included free liquor, and Ira drank greedily. It was the quickest way to blur the painful, heedless publicity to which he was subjected.

After his discharge he went home to Arizona, in the district called Bapchule. After the excitement of war and the hectic round of living which he had just experienced, Hayes' Indian home was not a place in which he could settle down at once. His was no longer a self-sufficient family, such as Hayes might have known in his own childhood, which certainly his ancestors had known before him. Without adequate water to grow crops, with landholdings reduced beyond any hope of economic livelihood even if there had been water, it was not a place for a returning warrior to rest and mend. Too many other mouths depended on the food he would eat.

With the help of the relocation program of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, he went to Chicago and found employment with the International Harvester Company. For a while things went well with him, then he began drinking again. He was picked up on Skid Row in Chicago, dirty and shoeless, and sent to jail. The Chicago Sun-Times discovered who he was, got him out of jail, and raised a fund for his rehabilitation. A job was secured for him in Los Angeles, where it was hoped that he might make a fresh start. Many organizations, including church groups, helped out.

Hayes thanked everybody gratefully, and said, "I know I'm cured of drinking now." But in less than a week he was arrested by Los Angeles police on the old charge. When he returned to Phoenix he received no hero's welcome. He told the reporter who met him: "I guess I'm just no good. I've had a lot of chances, but just when things started looking good I get that craving for whisky and foul up. I'm going back home for a while. Maybe after I'm around my family I'll be able to figure things out."

But the family home still did not have the answer. Across the road and across the fence which marks the Pima reservation, water runs in irrigation ditches. The desert is green with cotton, barley, wheat, alfalfa, and citrus fruits, pasturage for sheep and cattle. But the water and the green fields are on the white man's side of the reservation fence.

He tried once, in 1950, to plead the case of his people before government officials in Washington. He asked "for freedom for the Pima Indians. They want to manage their own affairs, and cease being wards of federal government."

But what he was asking had become infinitely complicated. It involved acts of Congress, court decrees, a landowners' agreement, operation and maintenance requirements. So complicated had it become that the lawyers and the engineers and the administrators hired by the government had succeeded only in reducing by half the acreage which the Pima Indians, in their simple way, had cultivated, on which they had grown surpluses of grain to sell to hungry white men.

But what he was asking had become infinitely complicated. It involved acts of Congress, court decrees, a landowners' agreement, operation and maintenance requirements. So complicated had it become that the lawyers and the engineers and the administrators hired by the government had succeeded only in reducing by half the acreage which the Pima Indians, in their simple way, had cultivated, on which they had grown surpluses of grain to sell to hungry white men.

Ira Hayes, coming back home, looked at the mud-and-wattle house, the ramada standing to one side, a few poor outbuildings, and knew that he would not find the answer there. He found it on the cold ground in a cotton field.